VII DIA INTERNACIONAL DE

JIGORO KANO

7th International Jigoro Kano Day

28 octubre 2017 / 28th October 2017

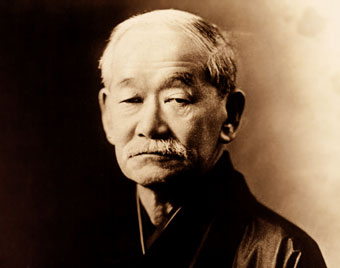

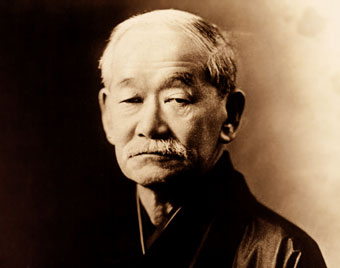

Jigoro Kano

(Mikage, 1860 - 1938) Maestro de artes marciales japonés que fue el fundador del judo, y única persona en el mundo con el título de sensei ('maestro'). Miembro de una familia acomodada de altos funcionarios imperiales, fue un chico de aspecto débil y enfermizo, tercero de cinco hermanos. En 1881, a los dieciocho años de edad, se matriculó en la Facultad de Ciencias Políticas en la Universidad de Kioto. El viaje a la capital, donde las artes marciales se hallaban en su apogeo en la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, había sido un momento largamente esperado por Kano, quien poco antes había comenzado el estudio deljujutsu (técnicas de combate encaminadas a vencer al contrincante con un mínimo de fuerza), obsesionado como estaba por aprender ciertas técnicas defensivas que le permitieran paliar su fragilidad física.

Jigoro Kano

Se inscribió en la escuela de Ryuji Katagiri, quien pensó que Jigoro era demasiado joven para practicar en serio, así que el joven se puso bajo la tutela de Fukuda Hachinosuke, cuyo método de enseñanza permitía a los alumnos desarrollar en cierta manera su propio estilo, ejercicios libres con varios movimientos (lo que se denomina randori). Cuando en 1879 el maestro murió repentinamente de una grave enfermedad, el joven de diecinueve años se convirtió en discípulo de Iso Masachi, en cuyo dojo permaneció por espacio de dos años practicando el jujutsu con tal dedicación que su maestro le hizo ayudante suyo y Kano empezó a impartir clases. Sin embargo, no estaba del todo satisfecho porque en su fuero interno sentía que debía continuar su aprendizaje antes de seguir con la docencia. Conoció entonces a Iikudo Tsunetoshi, maestro de la escuela Kito-ryu, y empezó a entrenar en sudojo.

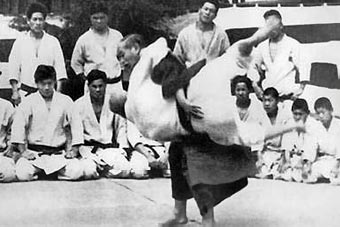

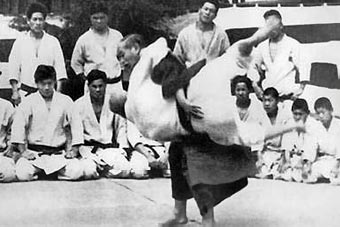

Le daba vueltas en la cabeza la idea de introducir ciertas reformas en el jujutsu, porque era evidente que su delgadez le dejaba en desventaja frente a un contrincante más corpulento, así que empezó a trabajar en técnicas que requirieran un mínimo esfuerzo. Desarrolló la manera de arrojar a su oponente al suelo con sólo un giro alrededor de los hombros, una técnica a la que dio el nombre de kata-guruma, y que pronto fue seguida de otras muchas, basadas en que había que desequilibrar al contrario para poder proyectarle luego con facilidad, mediante un giro de la cadera o de los hombros. No creó un nuevo sistema de jujutsu, simplemente aplicó una serie de principios científicos y eliminó aquellas técnicas que le parecieron lesivas o peligrosas, todo lo cual le llevó a disciplinar no sólo el cuerpo, sino también el espíritu.

En 1882, con tan sólo veintidós años de edad, fundó su primer dojo (en la actualidad, 'lugar de entrenamiento para las artes marciales', pero antiguamente se denominaba así la sala de meditación de los recintos sagrados) en el templo budista de Eisho-ji de Tokio con la ayuda de sus propios alumnos, a quienes otorgó los primeros cinturones negros. Su antiguo maestro, Iikubo, pasaba dos o tres veces a la semana por el Kodokan (como llamó a su escuela) para impartir sus enseñanzas a los discípulos de Jigoro. Un año antes, en 1881, había obtenido su graduación en la Universidad Imperial de Tokio, y empezó a dar clases de literatura en la escuela Gakushuin, una exclusiva institución para los hijos de la alta sociedad japonesa.

Simultaneaba su instrucción en el dojo con su trabajo en el colegio y la preparación de sus clases; en realidad, aplicaba las mismas técnicas pedagógicas con sus alumnos, tanto en eldojo como en el aula, basadas en una severa disciplina, no exenta de generosidad (se dice que ofrecía ropas y comida a sus discípulos pobres). Sin embargo, los continuados entrenamientos en el templo acabaron por deteriorar el suelo y las imágenes sagradas, así que los monjes le conminaron a abandonar el lugar. Finalmente consiguió que le dejaran construir un pequeño dojo en un edificio anexo al templo.

En 1884, pasó a prestar sus servicios en el Ministerio de la Casa Imperial; ese fue el año en que se establecieron finalmente las reglas del Kodokan (literalmente 'escuela para el estudio de la vía'). Aquel pequeño dojo inicial se había convertido en un gran centro al que acudían japoneses y extranjeros. Jigoro adoptó entonces el que sería el lema del judo: "Sólo a través de la ayuda y de las concesiones mutuas puede un organismo que agrupa a individuos en gran o en pequeño número encontrar su plena armonía y realizar progresos serios", y tomó como emblema la flor del cerezo (sakura). El éxito fue inmediato y, como era previsible, surgió una fuerte rivalidad entre el judo y el jujutsu, que asistía a su declive durante estos últimos años del siglo XIX. Hacia 1886, Kano cambió de nuevo el emplazamiento de su escuela a la residencia de uno de los personajes más influyentes de la Era Meiji, el barón Yajiro Shianngawa, lo que dio al judo el espaldarazo definitivo sobre el resto de las artes marciales.

El maestro en una de sus clases

En agosto de 1891 contrajo matrimonio con Sumako, la hija mayor del sensei Takezoe, en otro tiempo embajador en Corea. Tuvieron nueve hijos, seis hijas y tres hijos, uno de los cuales, Risei, llegó a ser la cabeza del Kodokan y de la Federación de Judo de Japón. Mientras tanto, continuaba su carrera de funcionario, en la que iba ascendiendo progresivamente, así que en 1893 fue nombrado Decano de la Escuela Normal Superior de Tokio. Su mentalidad progresista fue revolucionaria para el sistema educativo japonés, pues abrió las puertas a los estudiantes procedentes de las clases sociales más bajas y forzaba a los que procedían de la aristocracia a realizar tareas humildes para disciplinarlos.

En 1889 hizo uso de su posición oficial para viajar a Europa, donde realizó demostraciones de judo en la ciudad francesa de Marsella. Posteriormente fue enviado en varias ocasiones en misión oficial a China y Europa (1902, 1905 y 1912) para proseguir con sus enseñanzas de judo. Fue el primer japonés miembro del Comité Olímpico Internacional, cargo desde el que asistió a los Juegos Olímpicos de 1912 en Estocolmo, a los de 1932 en Los Angeles y a los de 1936 en Berlín; en 1915, el rey Gustavo de Suecia le impuso la medalla olímpica en recompensa a sus esfuerzos para promover el deporte dentro de un espíritu elevado.

Cinco años más tarde, en 1920, se jubiló para dedicarse por completo a la difusión del judo pero, para entonces, ya contaba miles de adeptos. El Kodokan, situado en Suidobashi, celebró su cincuenta aniversario en 1934 con una impresionante ceremonia a la que asistió el príncipe imperial y otros altos cargos de Japón. A su muerte, en 1938, dejó una obra escrita, Kodokan, en la que se exponían los fundamentos de su filosofía. En 1962 se construyó en Tokio un nuevo edificio, llamado Budokan, para reemplazar al Kodokan y dar cabida a maestros de otras disciplinas de jujutsu, como el aikido, y dos años después se consiguió que el deporte del judo fuera considerado disciplina olímpica. Las mujeres por su parte, no lo verían incluido en su programa hasta los juegos de Seúl.

______________________________________________________________

Jigoro Kano

Kano was undoubtedly of genius caliber, and, in his mastery of many intellectual areas of study, a genuine polymath as well. Combined with these talents was an extraordinary capacity for work, and a stubbornness about attaining the goals he had set for himself. It is difficult to imagine, when his father forbid him to study ju jitsu at age 16, that he would go out and do so anyway. From a skinny 90 pound 16 year-old, we see the results of his ambition to be physically stronger when at age 22, and still only 5'2" tall, he weighed an astonishing 165 pounds. Kazuzo Kudo recalled that Kano had broad shoulders and chest and big calves. "Shihan was so proud of his calves, he was always pulling up his hakama to show them off." Kudo also recalled Kano's own Judo skills: "I was surprised at how quickly he threw me."(1). He invariably treated all students in the same way. Saburo Nango, Kano's nephew, recalled that "Keichu Tokugawa, son of a former shogun, was treated no differently in Judo training than any of Kano's other students."(2)

Kano was thought of as a "confident and broad-minded president" by his peers at the Tokyo University, where he served as president.(3) As an instructor, he was "unusually" strict. His nephew, Jiro Nango, came to study Judo under Kano and recalled that, as a student, "I had to get up at 5 o'clock" every morning and help clean the rooms and the garden." (4) His son-in-law, Takasaki, recalled that Kano was easy to anger, but just as easy to laugh and had a keen sense of humor. "He laughed deeply when he was pleased," and was generally always seen to be smiling, even when angry.(5)

Kano did not smoke, but did occasionally drink sake. Kudo recalled that "he liked his sake and his face got red quickly when he was drinking," but he knew his limit and usually stopped before he had too much. "If he over-imbibed, he invariably got sick." He rejected the Japanese tradition of exchanging sake cups with fellow drinkers as unhealthy. Japanese farmers, among whom the tradition was particularly strong, invariably attempted to swap cups with Kano, and he would become angry.

At home, Kano lived in the tradition style of a "kokushi" father. Although he had tried to teach his son, Risei, Judo at home, Risei apparently had no talents in that area. Other than that, he had little personal contact with his children. He kept a refined distance from his children, and his word was law. His daughter Noriko recalled, in her book Recollections of my Father, that "when he returned home, he would go straight into the living room, which meant on most days I did not see my father at all." If they did, it was when they lined up at the front door to bid Kano "okaeri-nasai mase" as he arrived. This was the typical Meiji-era family structure, and Kano seemed to feel comfortable with this traditional setting. Still, "he wept when he heard of Noriko's death."(6).

Professionally, Kano was often at odds with his superiors over educational theory and teaching. He was an avid student of John Dewey's revolutionary approach, but not all Japanese educators were of the same mind. One writer noted that Kano never submitted a letter of resignation over such disputes, because of course Kano never thought he was wrong, they should resign, not him. He was sometimes accused of giving boring lectures, however, and once, when only three students showed up, he was so angry he declared that "Everyone in this course is dropped."(7).

He always took a personal interest in his Judo student's welfare. Even while he was a tough disciplinarian he made barley tea and rice mixed with lotus roots for his students at the Eishoji Kodokan, and provided his poorer students with practice clothes, which he even laundered.(8) Another student, Takasaki, recalled that after he graduated from Waseda University in 1925 and joined an army Imperial Guard unit, he received a telegraph from Kano: "Your father has been looking for a good wife for you. What sort of woman do you have in mind for a wife?" Three years later, Takasaki married Kano's youngest daughter, Atsuko. (9)

Kano's multiple efforts at organizing, developing, and spreading Judo, coupled with his work developing the Japanese educational system can only be viewed as remarkable particularly in view of his ongoing efforts to organize Japanese amateur athletics. He was founder and first president of the Japanese Amateur Athletic Union, bringing him a seat on the International Olympic Committee in 1909. There, he became "revered," but, as World War II approached, Kano saw the divisions and fracturing of mankind as inevitably leading to war. He blandly attempted to defend Japanese occupation of Manchuria on the grounds that China had been tearing itself apart with "warlordism," and that was true. He saw Japan as trying to help.

As the military took over more aspects of Japanese life, Kano resisted the use of Judo for military purposes. Over the militarists strenuous objections, Kano sought to have the 1940 Olympics held in Tokyo. "Sportsmanship is above war," he told one press conference. He succeeded, amazingly, at a time when Japan was seen as suspect and ruthless in its colonization of its neighbors. That Kano was successful can only be attributed to the great respect he had from the world, and also, undoubtedly, respect at his courage for seeking the games, to bring the spotlight of the world on Japan. America and England, both resolutely opposed to Japanese policies in the Far East, ultimately supported Kano's controversial bid.

It could not have been to reward Japan. Rather, the IOC delegates must have understood Kano's wish, that the idea of sportsmanship, of bringing humanity together, was of paramount importance in dangerous times. Kano needed to bring the Olympics to Japan to derail his government's reckless military preparations, to focus attention on them, as well as remind Japanese that they had a moral obligation to the world in return.

The IOC overwhelmingly approved Tokyo. But, on his way home, one newspaper writer in Seattle saw that Kano was tired, and seemed, already, disappointed. He was "a gracious, kindly little old man, whose heart was wrapped up in youth and amateur athletics," wrote Seattle PI sports editor Royal Brougham. He should have been celebrating his great personal achievement, but Brougham noticed that nothing "could hide the disappointment within." Kano had spent his entire adult life trying to build a new Japan. His Judo had tried to eradicate the ruthless, Nietschean concepts of old Budo. His school teachers had fanned out from Tokyo for over a generation, bringing Kano's enlightened ideas to every facet of Japanese society. His personal stature as defacto foreign minister, representing Japan on countless occasions, had given him a highly influential voice.

Kano was a devout pacifist. He would not, his children noted, even intentionally kill an insect. His seeking the Olympic Games was at odds with the more radical members of the military government in Japan. Kano was glad to chat pleasantly with Seattle newspaper men on his way home to Japan, in early May, 1938. "Outwardly, Jigoro Kano was confident that shot and shell in the Orient would not interfere with his country's elaborate plans for the 1940 Olympics.

"Those of us who were thrilled and awed by the never-to-be-forgotten scenes at the Berlin Games, and at Los Angeles four years before, can feel just a small part of the disappointment in Count Kano's soul. Nothing has contributed half so much to better understanding and friendly relations among men of different race and tongue as athletics."

" In his soul, he probably knew differently. Count Kano will not be there to witness the Olympic spectacle he planned and worked for."

Kano died on his way home, May 5, 1938, while aboard the Japanese ship, Hikawa Maru. His death was officially attrributed to pneumonia. "The doctors had a name for the disease but a heart heavy and broken from the shattering of his Olympic dreams probably contributed to his sudden death."

Within a few weeks of Kano's death, the government of Japan cancelled the games, and within a few months, invaded China from Manchuria. The prime minister and his cohorts were all avid proponents of Budo.

Back to Part Ten, "History of Kodokan Judo"

| | | |

| | | |

Kano, a "revered Olympian"

leads the IOC delegation at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games |

| | | |

Jigoro Kano, aboard the Hikawa Maru, May, 1938.

Memorial to Jigoro Kano

at the Kodokan | | | |

| | | |

| |

| | | |